The threat that comes from the Arctic

Russian researcher warns that methane emissions may dramatically speed up global warming.

Leila Marco e Rosana Bertolin

Tuesday | December 22, 2015 | 1:51 PM | Last update: September 22, 2016, 4:07 PM (Brasilia time)

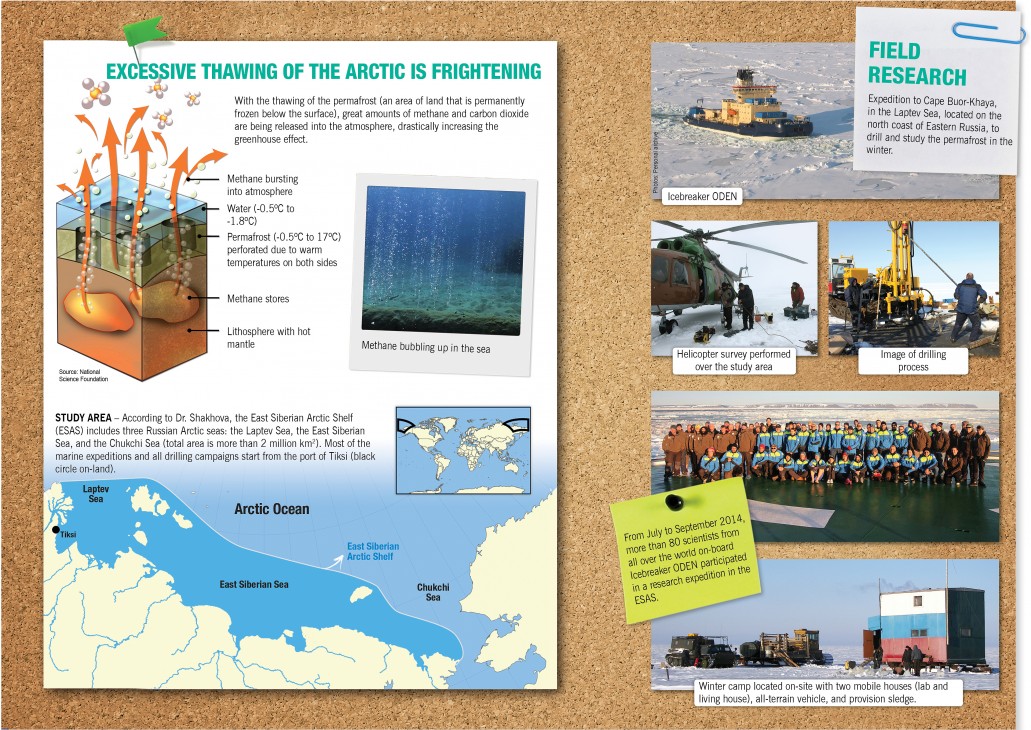

Very serious questions have been raised by Russian scientist Natalia Shakhova, who, alongside her compatriot Igor Semiletov, is leading a group of international researchers concerned with the growing release of methane (CH4) from the seafloor of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf (ESAS), located on the north coast of Eastern Russia. Their observations show that in some points the concentration of this gas is thousands of times greater than expected. According to the academics, in the summer, when the sea ice melts, CH4 can be seen bubbling up on the surface in continuous, powerful, and impressive seeping structures of more than one thousand meters in diameter.

In August, Shakhova, who is a research professor at the Tomsk Polytechnic University, in Siberia, Russia, and at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, in Alaska, United States, as well as a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, made room in her busy schedule to talk about the subject in an exclusive interview with GOOD WILL magazine. On the occasion, the Doctor of Sciences in Marine Geology and PhD in Medical Geography explained that the above-mentioned phenomenon, which has been mapped out by her and her colleagues since 2003 in one of the most remote and isolated areas on Earth, is the result of the progressive thawing of the permafrost (an area of land that is permanently frozen below the surface), below which the researchers calculate there may be millions to billions of tons of methane, one of the greenhouse gases whose capacity to retain heat is twenty times bigger than that of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Dr. Shakhova also commented on the impacts of her group’s discovery, highlighting an extremely worrying fact: “Arctic sources of methane have never been included in the global methane budget or considered in the global climate models, which aim to predict future climate scenarios for our planet.” In other words, the release of CH4 that occurs in that vast region may cause global warming to become even worse very quickly. Apprehensive about the possibility of this somber outlook becoming a reality, the researcher emphasized that, “Neither I nor anyone else on our scientific team has ever been to Brazil, but we know that the Brazilian people cherish family values. We hope that your values will spread over the entire world so that all the people living on our planet begin to care for each other and for Mother Nature as they would care for their own family members; this will make our world a much safer and happier place to live.”

GOOD WILL — Your team has brought significant warnings about the dangers of the imminent destabilization of the Arctic permafrost to the world’s scientific community. What is your research routine like at this site?

Shakhova — The East Siberian Arctic Shelf, where we are working, is the largest sea shelf in the world (2 million km2); a huge area of investigation. When we began our studies, nothing was known about methane emissions. . . . This was indeed like searching for a needle in a haystack. We were fortunate to find a few hot spots in 2003, and we believed there must be more; since then we have conducted expeditions at sea every year. In 2011 we began to drill into the permafrost that exists beneath the sea floor. We installed our drilling rig on the fast ice, extracted sediment cores, and investigated the current state of subsea permafrost. This subsea permafrost is a major factor controlling methane emissions in the ESAS. . . . Our scientific work at sea includes round-the-clock sampling and surveys. We do not get much sleep on our expeditions.

GW — What are the main challenges faced while carrying out fieldwork?

Shakhova — Besides the logistical difficulties, the Arctic is a harsh environment and working there is always a challenge, especially nowadays because the Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. The entire cryosphere is affected—sea ice, glaciers, and permafrost. Storms occur more often than before, waves grow larger, and encountering a so-called killer or rogue wave, as much as 100 feet in height, is a possibility; such a wave could sink our vessel in minutes or less. . . . Performing winter expeditions is becoming more difficult because the sea ice is becoming thinner, the number of breaks in the ice is increasing, areas of open water (called polynyas) are growing, and the ice break-up period is starting earlier. One year our expedition was nearly washed away by an earlierthan-normal pulse of melt water coming from the Lena River.

GW — What is the importance of the Arctic permafrost to the planet?

Shakhova — Arctic permafrost is made up of frozen ground on land and frozen sediments beneath the seafloor. In the ESAS, permafrost formed during periods of cold climate like the Pleistocene, 2.6 million to 11.7 thousand years ago. The last glacial period ended with the end of the Pleistocene, ushering in the current warmer Holocene. Glaciers tie up a lot of water in a frozen state, and therefore sea levels were lower in the Pleistocene than they are today by up to 100m; much of the ESAS is less than 50m deep today, so the shallow ESAS sea floor was exposed to frigid air temperatures. ESAS sediments froze as much as a few hundred meters deep and became permafrost. Permafrost stores a huge amount of organic carbon. If the sediments containing this organic carbon were to thaw, enormous amounts of methane and carbon dioxide will be produced and released to the atmosphere, dramatically increasing the greenhouse effect, which is already causing global climate change. Extensive and massive release of methane from destabilizing seabed deposits might have unpredictable consequences for our climate system. These consequences remain uncertain because Arctic sources of methane have never been included in the global methane budget or considered in the global climate models, which aim to predict future climate scenarios for our planet. The purpose of our investigations is to fill this gap in our knowledge, make the future more predictable, and ultimately help our planet and all the organisms on it, including us, to survive.

GW — Is it possible to predict the consequences of methane emissions for the planet?

Shakhova — The Arctic holds enormous amounts of methane as a pre-formed gas and also organic carbon, which might serve as a substrate for methanogenesis (formation of methane) when permafrost thaws. Fortunately, onland permafrost, which constitutes the greater fraction of permafrost on the globe, largely remains stable. Unlike on-land permafrost, however, subsea permafrost is experiencing drastic changes in its thermal regime due to the warming effect of seawater and other factors. Remember that the permafrost in the ESAS was formed during an ice age when the current ESAS seafloor was not under water and was exposed to frigid air temperatures. When the glaciers began to melt and the ESAS filled with water, the water covering those sediments was much, much warmer than the air had been, and inevitably the temperature of the frozen sediments began to rise. This is very disturbing.

GW — What can occur if the subsea permafrost thaws?

Shakhova — Subsea permafrost sealed off seabed deposits of methane for thousands of years, during which time methane kept accumulating in these deposits. . . . If this methane is released suddenly, in large quantities, the suddenly increased levels of atmospheric methane might cause unpredictable consequences for the climate of our planet. Unfortunately, our current knowledge is still limited and further speculation would be irresponsible. . . . We need to continue our investigations until we can determine mechanisms that could avert this scenario. Meanwhile, anything that can be done to decrease our emissions of greenhouse gases will be a step in the right direction.

GW — What are your expectations with regard to the 21st Conference of the Parties on Climate Change 2015 promoted by the United Nations in Paris?

Shakhova — I try my best to remain optimistic when it comes to international collaboration on climate change issues. I also realize that any decisions made and declarations announced should be constructive and feasible. To achieve this, decision- and policy-makers should be provided with unbiased and comprehensive information about the real processes and triggers driving the climate system out of order. I am afraid that there is a problem with the most influential institutions (for example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC), which many years ago appeared to be most progressive and foresighted, but have now become inert, conservative, and obstructive when it comes to accepting new knowledge and incorporating it into their realms. This can clearly be seen, especially when it comes to the Arctic region. If this situation remains unchanged, we will all pay a steep price.

GW — What is the biggest legacy you would like to leave humanity through your work?

Shakhova — The biggest legacy scientists could leave humanity is new knowledge that will help people keep our planet alive and healthy. What we do in the severe Russian Arctic, sometimes putting our lives at risk, we do for our children’s future; for all the people on the planet to be able to live a normal life.